PRACTISING CLOSE READING IN CLASS

Giving pupils the reading skills to succeed!

Paddy Salmon MA PGCE

Head of English SIS (Sèvres)

1993-2012

paddysalmon.wix.com/english-courses

INTRODUCTION

" Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—"

John Keats from On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer

About three years ago I received an email from an ex-Sèvrien science stream French pupil, who wrote to me from Imperial College, London, at the end of his first year there, studying Engineering. He asked after me and said I would probably be expecting news from him about how he had got on during the year etc. But he wasn't going to write anything about that, if I didn't mind, as it was all going along fine. Instead, he referred to a lesson on "Mrs Dalloway" the previous year, where I had challenged his Terminale class to tell me why they thought Virginia Woolf had written that Elizabeth stepped "competently" on to the omnibus going up the Strand towards Fleet Street, and why Woolf had repeated that same phrase for the journey back. I had asked them to think about what that "competently" might signify.

"I have been thinking on and off throughout this year spent in London about why she used that word 'competently' and I now think I have got the answer!" wrote Victor (a year too late to include it in his exam answers, for which, however, he had received excellent marks in both the oral and the written).

There followed two pages of reflection about how Elizabeth, who represents a new generation in the novel, was deliberately leaving her comfort-zone by taking a bus away from the "village" of Westminster towards Fleet Street (and the big, bad City) and about how important it is for her (we are given access to a flash of self-awareness, here, in the word "competently", as Elizabeth is now aware of her own sense of competence) and important for the reader to see that she is in command of her life and her future… and so on and so on. This was what 'competently' was supposed to signal here. None of this is particularly groundbreaking, perhaps, but I was touched that he should have been niggled by this one small detail. I think it says something about how literature can work on us, when we are reading attentively. We can read in all sorts of different ways, but sometimes it is the small details that can unlock things for us. Besides which, Elizabeth's important role in the novel could be easily overlooked somewhat...

This is NOT a teaching handbook as such and I would be the last person to want to try to systematise any such teaching. Nor is it, either, a replacement for any of the recognised works on close reading and practical criticism that are around. I started, in the Sixth Form, with I.A. Richards' "Practical Criticism" and William Empson's "Seven Types of Ambiguity", and as a teacher I regularly used John Peck and Martin Coyle's excellent book, "Practical Criticism" (with its invaluable techniques for finding "tensions" in close reading). I have also been very stimulated by books such as David Lodge's "Consciousness and the Novel" and "The Art of Fiction", and there are obviously far more to mention - including, very importantly, Adrian Barlow's "World and Time - Teaching Literature in Context", which I absolutely recommend as essential reading in this area.

This, however, is more of a quirky mass of personal enthusiasms and past lessons, which I have attempted to put into some sort of (vague) order here, in the hopes that others may find something of interest to help them with the difficult task of helping pupils to respond to and appreciate literature. It is governed by two main concerns: my wish to develop close, active reading with classes; and, beyond that, my sense of the importance of teaching literature "as a subversive activity" (cf. ''Teaching as a Subversive Activity" by Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner 1968. It's a bit dated now but the book had a profound influence on me at the time – in particular, with its insistence on the need to develop the right questions, and to be prepared to question everything).

None of any of this is very original, but it represents how I have been trying to teach literature for many years now, first in England for thirteen years in London comprehensives and west country grammar schools, and then in France at Sèvres for twenty-five years, while the OIB was developing around us.

1 The first idea, then, is that close reading is an active response to text. One should therefore get rid of notions that the teacher is “transmitting” knowledge as such, or that there are wrong answers and right answers per se, with the teacher at the front as final arbiter. I would prefer to look at it as the teacher sharing and "testing out" ideas, offering encouragement and direction to students, more often than not in pairs and groups, as they respond critically and sensitively to literature in all its facets.

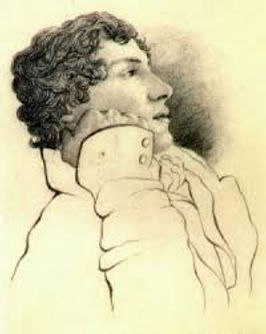

Keats' "On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer" gives us as readers two wonderful images of "looking into" books. The first one is exciting but passive: an astronomer sees a new planet swimming "into his ken". "Swimming" could suggest tears of excitement or joy, but this is still a solitary and passive experience. Far more interesting is the second image where we are given Cortez, who is, first of all, with "all his men", and secondly, using his "eagle eyes" actively to expropriate the Pacific, with all its golden possibilities. This, surely, is why Keats felt he needed to elaborate his comparison further in this sonnet all about reading and the experience of "looking into" things. It is this active and social reading "into", that we as teachers should be encouraging.

2 The second idea is that literature, unlike the sciences, deals with all the thorny problems of life (and love, conflict, happiness, pain and death), where there may be no clear answers and probably multiple viewpoints. If problems are complex or difficult, then it is likely that the literature which attempts to grapple with them will be complex and difficult, too, at times. Since we are all in this “boat” together, there are immediate reasons pedagogically for accepting a more “horizontal” classroom as opposed to a “vertical” top-down, traditional one. We all have to come to terms with feelings about love, death, society, loneliness, family or other conflicts, and so on, and, to that extent, we are all equal as readers of literature. In reading "closely" with a class or a group, we are trying to train young people to react to literature, past or present, to examine their own responses and thus to enlarge their experience through reading. Learning, therefore is shared and on-going (for teachers as well!). Students should therefore be encouraged to challenge everything, not excluding the teacher and the curriculum. If we are serious about "criticism", this is the road along which it is taking us all.

My own rule of thumb has been that all pupils, at whatever level, should always feel that they can challenge me or anyone else in the group on ANYTHING we are studying together, provided it is done courteously and with rational justification. How else can critical awareness be developed? And of course, therefore, tables should always be arranged in a circle, as much as possible, rather than all facing the teacher!

3 A third idea is that literature, unlike, say, the study of history, deals directly with questions of “art” and artistry– in a very wide sense, since both fiction and non-fiction can, and should, be read for their different dynamics and aesthetics in terms of their appeal to the imagination. To that extent conceptions about art, about form, structure and style, as well as content, will need to be widened and cultivated.

4 Fourthly, students should have access to different teachers, if at all possible. I was very lucky myself, that in my last two years at school I had 6 different English teachers – a classicist headmaster, an evangelical Leavisite, an unrepentant Marxist, an ardent feminist, a complicated Freudian psychologist and my father, whom I'd describe as an old-fashioned Romanticist (Keats, Brontës, Shakespeare et alii, top of the list). All of this led me to have a very enriched view of English studies and an awareness that no single vision of literature or teaching could or should predominate.

A typical (if we can allow such an idea) English class will therefore (ideally) be small (under 20 if at all possible). It is likely to be in a reorganised classroom, where tables are turned to form a circle. Small groups or pairs will form themselves at regular moments to discuss and argue, reporting back to the teacher and the group as a whole at other moments. Talk will be extremely important and must be encouraged in all its forms – informally, within small group discussions; more formally in presenting findings or debating in a more careful way. Heated debates: hesitant ponderings. There might be some team teaching at times, or teachers might swap classes from time to time, as we often do in Sèvres, particularly on our Revision Trips, to get different perspectives on texts. Crucially, too, students will be examining their own responses to texts, as well as being guided by the teacher.

5 Knowledge about texts and their contexts is, of course, crucial too, and also about how responses to texts have varied over the years. In this respect, I cannot recommend too highly Adrian Barlow's book "World and Time: Teaching Literature in Context". I can only hope that some of the ideas here may, in a much less complete way, run alongside his excellent training in close reading in context, going in somewhat the same direction.

6 The “climate” of the classroom will also reflect all the above concerns. The atmosphere will be warm and encouraging. Pupils will not feel intimidated about expressing and developing their views. Mistakes are important learning opportunities. Marks will not be thought of as tools to penalise but as a means of rewarding students for meeting certain criteria, which are transparent and known in advance. To this extent, our department always hammered out our own marking criteria (in line with the OIB criteria, UK KS3 criteria and other sources), reviewed them regularly and posted them in the public domain on the school web site.

7 The debating of criteria at different levels is, I suggest, of crucial importance for English teachers in a department and is part of the on-going debate about teaching methods, aims and styles which needs to take place. Teaching aims and objectives HAVE to be harmonised in a good department. While there should, of course, not be a total orthodoxy, departments nevertheless need to be standardised so that all participants (students, parents and teachers) can have confidence in the teaching aims and outcomes.

Practising "close reading", and all that it entails, is therefore what this particular project is all about. It aims to give direction and support to teachers by outlining some strategies and lessons that can be applied practically in the classroom. It's very much a personal selection. And teachers, too, should feel free to challenge any of the ideas or conclusions I present here.

8 My last idea, and it is perhaps the most important of all, is that literature is enormous fun and one should never be bored, or boring, teaching literature. It's so entertaining because it is more than just "entertaining": it's utterly engrossing. Bill Shankley, the old Liverpool manager, once said, "Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that." I feel the same is true of literature. This is not just work for an exam, but a basis for a lifetime of living and being. Once pupils get this, they will have got a LOT. I received an email in the same week as Victor's from another ex-pupil saying how much she had enjoyed poking her head out of the tent flap that summer and shouting up to the sky,’Busie olde foole, unruly Sunne’.

We live in an age where a lot competes to attract children's attention, in an instant, ready-made fashion. Here, we should be encouraging our students to consider more carefully, to think for themselves independently and to be able to formulate their judgements sensitively, coherently and persuasively.

N.B. Here is Keats' poem in full:

On First Looking into Chapman's Homer

by John Keats

Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

For another wonderful poem, which engages with ideas of reading, turn to his "Ode on a Grecian Urn", which I look at in Section 5 on Irony and Aporia. And, for a more modern consideration, the poem by Wallace Stevens in Section 6 on Difficulty and Complexity is, I find, very stimulating too in a diiferent sort of way.

PRACTISING CLOSE READING WITH CLASSES

Still available....

Fleet Street in the 1920s with omnibuses