PRACTISING CLOSE READING IN CLASS

Giving pupils the reading skills to succeed!

Paddy Salmon MA PGCE

Head of English SIS (Sèvres)

1993-2012

paddysalmon.wix.com/english-courses

14 THOMAS HARDY'S 1912-13 POEMS

On the 27th November of 2012, it was exactly 100 years since Emma Gifford died. She was Thomas Hardy's first wife, whom he met in 1870 in the remote parish of St Juliot near Boscastle in Cornwall. Hardy had been sent as an architect to oversee restoration work on the church of St Juliot.

Leaving his home in Bockhampton, near Dorchester in Dorset, in the early hours of 7th March, Thomas Hardy reached his destination late in the evening. In those days, before the coming of the Great Western Railway, Cornwall must have seemed as wild, remote and exotic, even, as somewhere like Morocco today.

At the door of The Rectory he was greeted not by the clergyman, nor by the Reverend Caddell Holder's wife, but by her attractive sister, Emma, who was almost the same age as Hardy, 29. Emma was a striking woman with very distinctive thick golden hair, which tumbled in curls about her shoulders. She was drawn to this learned young man, who also wrote poetry and had just finished writing his first novel two days before and in the days that followed, showed him around the beautiful, rugged coast riding her pony.

I rode my pretty mare Fanny and he walked by my side and I showed him some more of the neighbourhood -- the cliffs, along the roads, and through the scattered hamlets, sometimes gazing down at the solemn small shores below where the seals lived, coming out of great caverns very occasionally. We sketched and talked of books: often we walked down the beautiful Valency Valley to Boscastle harbour where we had to jump over stones and climb over a low rail by rough steps, or get through by narrow pathways to come out on great wide spaces suddenly, with a sparkling little brook going the same way, into which we once lost a tiny picnic tumbler, and there it is to this day no doubt between two small boulders.

-- Emma Hardy: from Some Recollections, ed. Evelyn Hardy and Robert Gittings, 1961

Vicki, my wife, and I know Boscastle and the area around very well. She used to go there as a child on holiday, staying with her parents in a boarding house run by two elderly sisters, the Misses Old. Meanwhile, unknowingly (this was when I was about 14 and she was 12), I was holidaying with my family nearby in Polzeath, a few miles to the west.

In 1976, just before we got married, we camped at the top of Rusey Cliff, just by St Juliot Church, and explored the region, going for drinks in the evening at The Cobweb, a friendly pub in Boscastle where Bea played the piano and everybody sang songs together. We used to walk down the Valency Valley and I remember looking, idiotically, for the little "picnic tumbler" that Emma and Tom lost in the stream running down to the sea. The chances of finding it over a hundred years later were very slim.

At Castle Boterel

by Thomas Hardy

As I drive to the junction of lane and highway,

And the drizzle bedrenches the waggonette,

I look behind at the fading byway,

And see on its slope, now glistening wet,

Distinctly yet

Myself and a girlish form benighted

In dry March weather. We climb the road

Beside a chaise. We had just alighted

To ease the sturdy pony’s load

When he sighed and slowed.

What we did as we climbed, and what we talked of

Matters not much, nor to what it led, ―

Something that life will not be balked of

Without rude reason till hope is dead,

And feeling fled.

It filled but a minute. But was there ever

A time of such quality, since or before,

In that hill’s story ? To one mind never,

Though it has been climbed, foot-swift, foot-sore,

By thousands more.

Primaeval rocks form the road’s steep border,

And much have they faced there, first and last,

Of the transitory in Earth’s long order ;

But what they record in colour and cast

Is—that we two passed.

And to me, though Time’s unflinching rigour,

In mindless rote, has ruled from sight

The substance now, one phantom figure

Remains on the slope, as when that night

Saw us alight.

I look and see it there, shrinking, shrinking,

I look back at it amid the rain

For the very last time; for my sand is sinking,

And I shall traverse old love’s domain

Never again.

Thomas Hardy 1913

Here is an essay I wrote about this poem many years ago:

The poem retraces a memory of the poet’s past, when he was with a girl in spring on a hill at 'Castle Boterel'. (We know, in fact, that this person is Emma, whose "phantom" now haunts him so strongly in his memory.) Although he says that what they did or said there “matters not much”, it is the quality of the memory that is so important (“A time of such quality”) and it is so intensely recreated that he feels, as an old man, he can actually see the “phantom figure” of his past. The intensity of the emotion in the poem is due first to the happiness he felt and secondly to the feeling that his life is nearly over and that he will never experience anything like this ever again. The poem therefore ends on a melancholy note, which borders on despair even.

The poem begins with a matter-of-fact description of the poet, who is driving to a highway in “drizzle”. The weather sets a sombre mood, perhaps symbolic of tears even (“glistening wet”) as he recalls the scene of long ago, when he and this "girlish form" stopped to climb the same hill on foot “to ease the pony’s load”. What he insists upon is the special quality of that moment and he does not share with us, or even comment upon, what they did or said, as if the moment were too private and personal. In the fifth stanza he emphasises how this “moment” can be imagined as becoming recorded in eternity, since the rocks beside the road have recorded “in colour and cast” their passage. It is as if nature has the power to record human instants, in the same way that footsteps can be recorded. Since the poet, too, is busy recording the moment, this offers a comforting parallel to the business of writing. What the poet is doing is as natural and as long-lasting as time itself.

Time, as an idea, figures very strongly in the poem. The memory is first located in March, very particularly, in spring, a traditional time of love and renewal. “Primaeval rocks” and “Earth’s long order” are referred to also, as if the poet were becoming increasingly aware of time and eternity at this stage of his life. Time is even personified like some tyrannical schoolmaster with “unflinching rigour In mindless rote”, suggesting that the cycle of life, “rote”, is as hard and senseless as having to learn things off by heart or by rote.

It is this awareness of time passing, so relentlessly and meaninglessly, which leads to the apparent despair of the last stanza. The repetition of the word “shrinking” suggests that not only is the vision of the girl fading, but that the poet’s whole life is vanishing. The rhyme with “sinking” accentuates this negative feeling, as the poet feels the sand in his hourglass running out. There is a resigned weariness about the last two lines, where he faces the fact that he will never fall in love again, described here somewhat heavily as “I shall traverse old love’s domain”. The Latinate words “traverse” and “domain” convey this weight of sadness, which is reinforced further with the last emphatic line of just two words, with a lot of stress on the first and last syllables of “Never again”.

When we look more closely at the way the poem is constructed, we notice a certain contradiction between the melancholy tone and the rhythms chosen. The rhythm is often anapaestic, as in the first two lines, which gives the writing quite a jaunty, lively appearance, more appropriate to a song, perhaps. This is particularly apparent, say, in such lines as,

- / - - / - - / - / -

It filled but a minute. But was there ever

- / - - / - - / - - /

A time of such quality ever before

This musicality, however, which suggests the positive, lively vividness of their love springing up, is always interrupted by the heaviness of the final line of each stanza, with only two beats to the line, suggesting something limping or incomplete. The heaviness of the 5th lines is most fully exploited in the final stanza, as we have seen, with its terrible finality.

The title of the poem seems to place it geographically, so that as well as being fixed in time, with a date at the end, even, it is also located in terms of space. This also gives a certain poignancy to the act of recalling this scene. The poet seems to want to assure himself, and us, that it really happened, and that not only he, the poet, has recorded it for eternity, but the rocks themselves have also done this. It is as if he feels that their love must have been so strong that it had the power to impress itself on the earth. This is the only really positive aspect of this memory: that it took place, really, and has been recorded not only by the poet but the natural world too. This may not be very reassuring, but it is the only reassurance offered in the poem.

In the end, it is a sad poem, recalling perhaps a moment of pure happiness but realising that the moment has gone forever and can never be repeated now except in a poem. It is a poem about love, but it is also very much about time, which is seen as a force of illogical destruction, capable of “ruling from sight The substance now”. Nevertheless, the act of remembering and recording is vitally important in the poem. Art and poetry, like the rocks the couple passed, records, reflects and remembers. This is the only way that “Time” can be combated, even though the sand in the hourglass will sink inexorably to the end.

Hardy's poetry is extraordinarily visual. Turn to the end of "The Noose" (Section 18) to discover a superbly dramatic and visually ' cinematic' poem called 'The Harbour Bridge'...

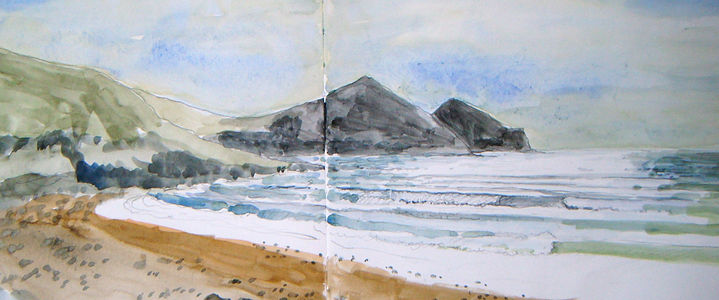

Rusey Cliff

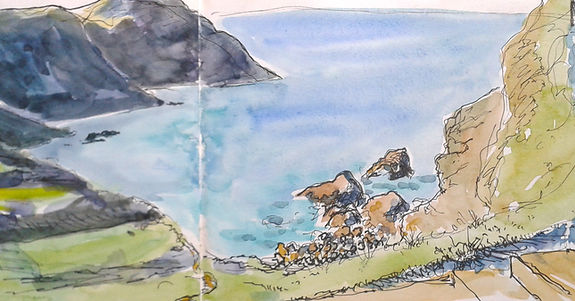

Boscastle Harbour

Boscastle High Street (then)

The main road, with all the modern traffic, which runs along the coast, now bypasses the original main road through the town, which is a narrow and very steep little road, where the Misses Old's house still stands with its dark slate roof. It is this old road, which Hardy writes about in 'At Castle Boterel' (his name for Boscastle).

In March 1913, four months after Emma had suddenly died, Thomas Hardy made a special "pilgrimage" back to the places near Boscastle where their love had started. He obviously felt a lot of grief, but also guilt, for over the years their love had decayed. They may have still cared for each other, but it was a childless marriage, and for a lot of the time Emma had been left on her own, while Thomas was the focus of enormous public attention as both a novelist and poet. The "pilgrimage" was in part an investigation into what had gone wrong, as well as a celebration of how wonderful their love had been, by contrast, in the early days.

I find these poems of 1912-13 very powerful and moving and would like to examine one particular poem here. We, also, have walked often up this street, and it is very steep – so it is easy to imagine a pony having difficulty dragging two people up to the top, where it meets the highway, or now the main road.

What may be difficult at first is realizing that there are two journeys being made in this poem: one is in the present, in rain, where he is alone; the other, "in dry March weather" refers to March in 1870, when he and Emma were together in Boscastle.

The landscape is a haunting one and I love trying to sketch it. The harsh black rocks are besieged by the Atlantic ocean, which rolls in from the west; there is no land between this coast and the eastern seaboard of America. The surrounding hills are high; the small fishing coves are narrow and huddle from the blast of the elements. It is only about ten years since Boscastle experienced a terrible landslip, which caused devastation in the little town.

Close-up of some of the "primaeval" rocks forming the road's "steep border. Hardy imagines them "recording" their passage as he and Emma passed them.